|

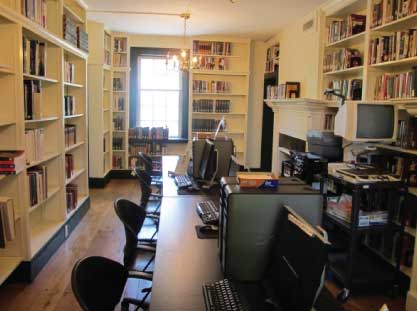

In 2010, Preservation Alliance of WV listed the Old Greenbrier Count Library on the WV Endangered Properties List, a collection of at-risk historic properties worthy of being saved. The property was especially notable for its construction date of 1834 and its original use as a law library by the jurist of the State Supreme Court of Virginia. Since its listing, this property has undergone quite a transformation and is now open to benefit the community. In October 2012, the New River Community and Technical College Greenbrier Campus celebrated the opening of the historic structure for its college library, which serves all five campuses, as well as the general public This project began in 2007 when the old Greenbrier County Library closed its doors, and shortly thereafter the owner, the City of Lewisburg, leased the building to the New River College. This partnership has allowed for the renovation and restoration of the building with work highlights including a new roof, new heating and air conditioning system, repaired wood floors, fresh paint, and rehabilitated historic wood windows.

Preservation Alliance is delighted to see this building reopened and the project goals come to fruition. We congratulate and commend the City of Lewisburg and the New River Community and Technical College for the reuse and return of this historic gem to its library roots. It often takes many years and much convincing for city governments to see the benefits of historic preservation. The City of Lewisburg, however, is unique in that it has supported historic preservation for many decades and encourages great projects like this one. We know why you’ve been deemed America’s “Coolest Small Town.” Keep up the great work! If you would like to comment on the future of the Blair Mountain Battlefield, you have until November 24th.

The West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection is accepting public comments until November 24th about the permit renewal request for the Adkins Fork Surface Mine. The permit boundaries encompass much of the Blair Mountain Battlefield and specifically White Trace Branch and White Trace Ridge – the two most promising sites for historical and archaeological information about the miners’ army. You can send your letters in response to Renewal of Adkins Fork Surface Mine S-5005-03 to: West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection, 1101 George Kostas Drive, Logan, WV 25601 If you do not know much about Blair Mountain Battlefield, please know that it is one of the most important Labor History sites in the United States and is considered to be the largest armed uprising on American soil since the Civil War. Please contact [email protected] if you have questions about the permit. If you would like to know more about Blair Mountain Battlefield, please continue reading. In the early twentieth century, coal alone fueled American industry. Work stoppages threatened steel production and the railroads, and political and economic pressure to maintain order in the coalfields allowed coal companies a great deal of latitude. Increasingly, however, mine workers began to organize as a way to withstand the industry’s back-breaking demands and garner a small piece of its extraordinary profits. These efforts were consistently resisted by the coal companies, whose suppression of the unions were also supported by a widespread national fear of Bolshevism following the Russian revolution. By 1921, southern West Virginia was ripe for violent confrontation. More than half of the state’s one hundred thousand miners were organized, but the union had largely failed to organize southern coalfields, which produced the region’s best specialty coal. The United Mine Workers of America believed that organizing the southern coalfields would improve working and living conditions for the miners, in addition to securing the survival of the union. At the time, coal companies enjoyed a great deal of political influence, and martial law was regularly employed to quell unrest. Lacking a National Guard, martial law in West Virginia meant that local law enforcement, including “deputies” in the pay of coal companies, exercised an inordinate amount of power, enabling widespread violence against miners and their families. The governor regularly requested the support of federal troops in disputes, but was usually rebuffed by federal officials, who did not want to set a precedent for the use of the Army in times of civil unrest. Following several violent conflicts, including those memorialized in the John Sayles film Matewan, Bill Blizzard, Frank Keeney and Fred Mooney of the District 17 United Mine Workers of America assembled 600 armed miners near Charleston for a march to Mingo County to demonstrate their solidarity, gathering additional miners to their cause as they advanced. Although no count was ever taken, it is likely that the miners’ army grew to at least 7,500, and may have surpassed 10,000. They intended to sweep through the southern counties of West Virginia, unionize workers and drive out the hired gunmen who guarded the coalfields and terrorized the miners. Meanwhile, Logan County Sherriff Don Chafin, whose salary was heavily subsidized by coal companies, learned of the miners’ intentions and began organizing local recruits to help stop the march. Hundreds of volunteers from across southern West Virginia flocked to Logan town to “do their patriotic duty” and end the rebellion by joining Chafin and his deputies, many of whom were also in the pay of coal companies. In the end, approximately 3,000 men comprised Don Chafin’s defensive force. The Battle of Blair Mountain took place between August 30 and September 4, 1921. Spruce Fork Ridge formed a natural dividing line between union and non-union territories. On August 30, the miners began their assault on Blair Mountain. Defensive positions blocked the miners along on the upper slopes of the ridge, with particular concentrations at the gaps: Mill Creek, Crooked Creek, Beech Creek and Blair Mountain. Here the defensive force dug trenches, felled trees, blocked roads, built breastworks and placed machine guns. Most of the hostilities between the two groups occurred along the fifteen-mile ridgeline, reflecting the miners’ use of natural pathways up and over the ridge to breach Chafin’s line. During the battle, private planes organized by the defensive militia dropped as many as ten homemade bleach and shrapnel bombs at Jeffrey, Blair, and near the miners’ headquarters on Hewitt Creek. In Charleston, eleven Army Air Corps pilots arrived, led by Billy Mitchell, a pioneer in aerial bombardment who was eager to experiment with the strategy. While troops were used in labor disputes throughout the nation during this era, West Virginia alone bears the distinction of having been the focus – and potential target – of military aircraft. Fortunately, the Army did not allow Mitchell to bomb the miners; the military planes performed reconnaissance flights. The end of the battle began with the arrival of federal troops on September 3. Six hundred miners, many of whom were veterans of World War I, formally surrendered rather than fight the soldiers. Far from considering the Army as an enemy, the miners considered the soldiers to be brothers and refused to fire on them. In the end, despite the valiant charges of a few miners and close-range gunfight at Blair Mountain itself, there was little face-to-face combat. Visibility was so limited by the thick, late summer underbrush that few combatants actually saw the enemy. Lon Savage, who wrote the most authoritative account of the battle, sets the number of documented deaths at sixteen–all but four from the miners’ army. But the defeat heavily damaged the UMWA, which lost members and territory in the wake of the battle. Although they did not win the Battle of Blair Mountain, the miners accomplished a great deal in their revolt. It forced national scrutiny of their situation in the press and in the federal government. They amassed sufficient force to require intervention by the United States Army, and they broke down racial and ethnic barriers to the solidarity they would need later when they did organize. Following sanctioning legislation in the 1930s, the UMWA became the leading force in organizing the nation’s industrial workers. UMWA president John L. Lewis formed the Congress of Industrial Organizations in 1937, which spearheaded the struggles for unionization in the auto, rubber, steel and other industries. As with other wars, this battlefield must be considered an important part of a larger effort. The events at Blair Mountain are overwhelmingly significant to the history of labor in the United States, because they set in motion a national movement to better the conditions of working people by demanding the legalization of unions and the use of the federal government to protect workers’ rights. |

News and NotesCategories

All

Archives

May 2024

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive e-news updates on historic preservation news and events in West Virginia.

|

Get Involved |

Programs |

Contact UsPreservation Alliance of West Virginia

421 Davis Avenue, #4 | Elkins, WV 26241 Email: [email protected] Phone: 304-345-6005 |

Organizational Partners:

© COPYRIGHT 2022 - PRESERVATION ALLIANCE OF WEST VIRGINIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed