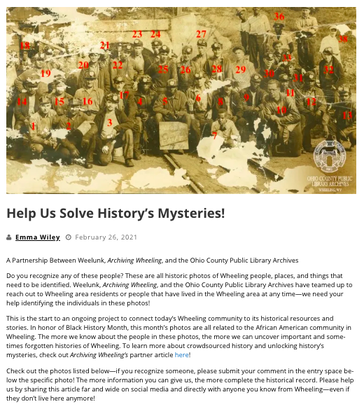

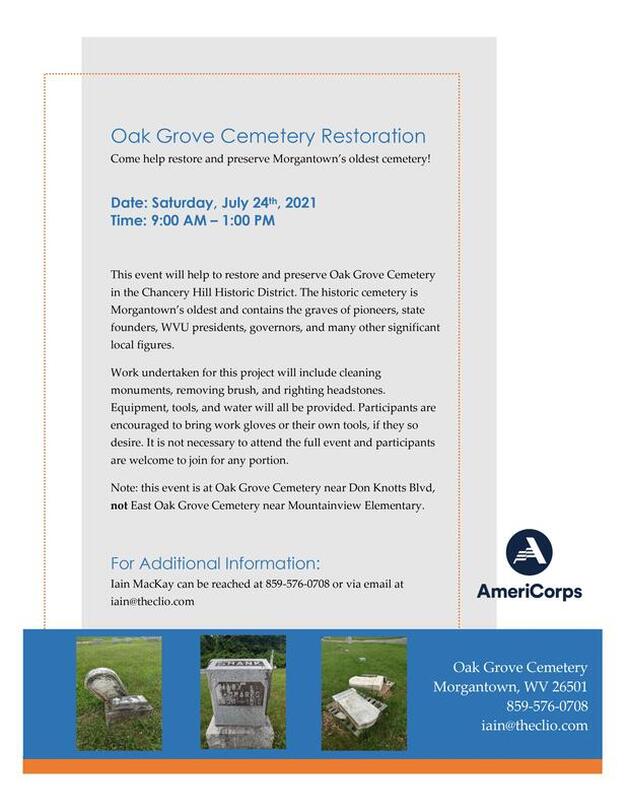

Hillsboro, WV, is a small town that packs a big historical punch. It’s home to the Pearl S. Buck House, Watoga State Park, and another lesser known gem – the Pleasant Green Methodist Episcopal Church. This historic African American church is so modest and unassuming that most passersby probably barely even realize that it’s there, but I’ve been fortunate enough to learn its heartwarming history and assist in its restoration during my time as an AmeriCorps Member here in West Virginia. I was first introduced to Pleasant Green in October 2019 while serving with the Appalachian Forest National Heritage Area’s Hands On Preservation Team. It was the first month of our service term and my first time doing official preservation work in the field, so I knew almost nothing about what I was doing and even less about the site itself. We were greeted by Ruth Taylor, Secretary of the Pocahontas County Historic Landmarks Commission and the church’s next-door neighbor, who told us all about Pleasant Green’s history. Built in 1888, the site was specifically designated at the time of sale for use as a church and school for the growing number of black families in and around Hillsboro. Pleasant Green was a branch of the African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Church, an African American-based denomination founded in Philadelphia in the late 1700s that grew popular throughout West Virginia following the Civil War. The congregation built and maintained the structure themselves with any materials they could scrape together, making Pleasant Green a true testament to people doing the best they could with what they had. The church remained a cornerstone for the local black community all the way up through the 1970s, acting as a place of social gathering and of education as well as one of worship. The adjacent cemetery became the final resting place for most of the congregation as well, with approximately 50 marked graves and many more unmarked ones suspected. Two of the people buried there were not just beloved community members but notable historical figures: “Miz Eddy” Washington, a well-known cook at Watoga State Park and former employee of the family of WV Governor Wallace Barron, and Gordon Scott, the first African American to become Superintendent of a WV State Park. Over the years, as families moved and the once-thriving congregation dwindled away, the church unfortunately fell into disrepair. On top of the chipped paint, rotting wood, pest damage, and other woes that typically plague old buildings, a fierce hailstorm in 2016 broke the glass in almost every one of the windows. The hail damage was especially disheartening, as it left the interior extremely vulnerable and destroyed multiple panes of rippled, amber-tinted “rootbeer glass” – a simple but beautiful decorative element that would have been very costly for the congregation and a point of pride on the otherwise unadorned structure. Luckily, Ruth was able to have the Hands On Team come in to repair and reglaze the historic wooden window sashes (saving and reusing all the surviving rootbeer glass in the process). At that time, however, the team and I were not able to carry out some additional work that we realized needed to be done to the windowsills. So, when I finished that service year and began my current one with the Preservation Alliance of West Virginia, I already had a plan in place to return to Hillsboro for my upcoming civic service project. There are four large windows on the body of the church and two very small windows on either side of a vestibule that was added to the front façade at a later date. Because the larger windows were paired with equally large sills cut from single pieces of old growth hardwood, those four sills all remained in relatively good condition. These simply needed to be scraped, treated with consolidant to reharden the “punky” (or softened) wood, and repainted. The sills for the smaller windows, on the other hand, were much worse. The vestibule was a poorly constructed addition using lower quality materials and has not aged well as a result. Nearly one third of each of these two sills had completely rotted away, making a full replacement necessary for both. Fortunately, these sills were only 1-inch thick boards inserted very simply into the overall frame, so replacing them wouldn’t be very difficult (I hoped). After visiting the church to make this assessment in Fall of 2020, Ruth and I planned for me to come back and complete the project in conjunction with a cemetery cleanup event to be held on Earth Day of 2021. I then spent the rest of the Winter being anxious and concerned that I might have committed to a project too big for one novice preservationist to successfully complete solo (since, as anyone who has ever worked on an old building can tell you, you never know what you’re going to find when you start poking around and even the simplest-seeming projects can quickly turn more complicated). Thankfully, Ruth helped put my mind at ease by reminding me that Pleasant Green has always been what she lovingly calls a “patchwork church” – it’s not all perfect, and it doesn’t all match, but everybody doing their small part to keep it stitched together over the years is what the true spirit of this place is all about. So, with that reassurance in mind, I returned to Hillsboro this past April and got to work. Everything miraculously went according to plan, and I was even lucky enough to be joined by another volunteer who was a master carpenter and could help me make the cuts on the new replacement sills. As I worked on the sills, other folks cleared away the overgrown brush from the cemetery or cleaned up the inside of the church to turn it into a community space once again. At the end of the day, as I stood back and looked around at all the progress that had been made, I couldn’t help but remember how the site looked when I first arrived to work on the windows two years before. The church’s restoration and continuing survival is truly a product of 130 years of collaboration and faith, and I’m so proud to have been a part of it. Kelsey RomerKelsey Romer is the Preserve WV AmeriCorps member serving with the West Virginia Brownfields Assistance Center's BAD Buildings Program during the 2021-2022 service term.  How do you engage the community with history during the time of COVID and social distancing? As more of the population gets vaccinated and the country starts to open up, many historical institutions and organizations are itching to restart in-person programming and events. However, the pandemic and the shift to everything virtual opened a door to creatively exploring ways to get communities to participate in local history. History’s Mysteries is a digital crowdsourcing partnership project between Weelunk, Archiving Wheeling, and the Ohio County Public Library, that solicits photo identification help from the Wheeling community. As the primary history collecting archive in the county, the Library has hundreds of photos of Wheeling people, places, and events that are unidentified. While these photos are important snapshots of Wheeling’s history, our knowledge is limited when they are unidentified. Once a month, we choose five photos based on a theme from the Library Archive to feature on Weelunk with an entry form where people can submit identification information. Our two goals were: 1) to get photos identified and therefore enrich the historical record, and 2) to engage the local community in the history that it has created. The reason for including the community in this form of creating history is because “historians have an important job of verifying, analyzing, and interpreting history, but it is the entire community that is responsible for maintaining and expanding the stories, records, and narratives that create the foundations of their society. Sometimes history’s mysteries just need someone with the right key.” Through History’s Mysteries, people who had never stepped foot into the Library recognized their mother or grandmother online--in some cases, they were photos they had never seen before. Expansion of the internet and digital technology has made it possible to reach a wider audience and engage with people who may not walk into the physical space of the Library. To increase our chances of identifications, we leveraged social media to get the project in front of as many people as possible. In addition, since many of the photos are older and therefore would only be able to be identified by the older population who is less likely to be on social media, the Library printed and distributed brochures with the photos for those who prefer paper. Not only does History’s Mysteries allow us to restore identities to the unnamed, but it educates the community on the resources and services the Library provides. When we started this project, we told ourselves that even just one identification would make this project a success in our book. One identity, one story, one life remembered would be worth it. Yet, we are pleased to report that with three monthly editions of History’s Mysteries under our belt, we have identified twenty-eight people so far! If you know anyone with connections to Wheeling, please forward them our History’s Mysteries Project--we are always trying to fill in the gaps! Emma WileyEmma Wiley is the Preserve WV AmeriCorps member serving with Wheeling Heritage during the 2021-2022 program year.  The Foreman Massacre took place on September 26, 1777 at the Narrows just north of Glen Dale, WV. Captain William Foreman and twenty-one militiamen from Hampshire County, Virginia were killed in an ambush by indigenous warriors. In 1835, a light horse company in Elizabethtown (now Moundsville, WV) raised money for and put up a sandstone memorial headstone at the Narrows where Foreman and his men’s remains were buried after the attack. Then in 1875, the stone and remains were moved to Mt. Rose Cemetery in Moundsville, WV by the County Court (now County Commission). The stone was placed in a concrete puddle in 1974 and is in very poor condition. The sandstone is cracking off on the front and back of the stone and there are many chips and cracks on the sides. The front has the historic inscription on it so will not be addressed in my civic service project because a skilled mason conservator would be needed to repair it. The back, however, is something I can help with. I have done a great deal of research on gravestone preservation over the last few months. I consulted skilled conservators Bekah Karelis and Sarel Venter of Adventures in Elegance based in Wheeling for advice on my project. Funding for my project is still pending but I purchased Natural Hydraulic Lime 5.0 from Otterbein and a consolidant from Bellinzoni called Strong 2000 that will be used in the preservation work. First, the damaged part of the stone that is falling off will be removed and the consolidant will be applied with a paintbrush. The stone will be completely saturated with distilled water and the lime putty will be plastered on and covered with wet burlap to cure. Once dry, it will be lightly sanded down until flush with the original stone. Then the cleaning process will begin with distilled water and a soft bristle brush to remove the green organic growth and black carbon residue. In the heavily soiled spots, D/2 Biological cleaning solution will be used. Once these steps are completed, the stone will look better and be preserved for many years to come. Pending additional funding, I would like to also take the project further and place a clear acrylic box around the stone to protect it from weather and pollutants. I also would like to place a granite plaque next to the Foreman Stone that has the inscription written out so it is easier to read, a summary of the massacre, and the stone’s journey from the Narrows in 1875. Bekah and Sarel also recommended the concrete puddle surrounding the stone be lifted out of the ground and a plastic sheet be placed under it to further help protect the stone from weathering. Once this project is completed, this portion of Marshall County’s Revolutionary War history will be looking its best! Evan WennerEvan is the Preserve WV AmeriCorps member serving with the Cockayne Farmstead for the 2020-2021 service year. When starting the process to identify potential sites for a Historic Property Inventory (HPI) form I was able to work off another Preserve WV AmeriCorps member, Iain Mackay's work and that of another Preserve WV AmeriCorps member who had done some work compiling West Virginia Green Book sites and determining which were extant, demolished, or questionable. It took me a couple hours of searching to find possible sites to research. I knew of some sites in Jefferson County, but discovered that HPI forms existed for those and I decided to find a site closer to home so that I could go take pictures if needed. Using Google Maps and preliminary internet searches I could not solidly identify or find information on any of the possible Fairmont sites, so I moved my focus up to Morgantown to try again. My colleagues had already determined that two of the five Morgantown sites no longer existed, and the remaining three were all tourist homes (individual homes that would offer lodging). The three tourist homes in Morgantown were: “Okey Ogden—1046 College Ave,” “Mrs. Lizzie Mae Slaughter—3 Cayton Street,” and “Mrs. Jeanette O. Parker—2 Cayton Street.” Unfortunately, Google Maps is not great in that area and has no street view on Cayton Street, but I was able to determine that 1046 College Avenue did exist and real estate information indicated that the existing structure was the correct age to have been Okey Ogden’s Tourist Home in the 1950s. Next I turned to Ancestry to dig into the census records and find any information on Ogden. I could find him and his family in the census records between 1900 and 1940 in different homes in Morgantown, including the 1046 College Ave address starting on the 1930 census. I also discovered that Ogden was a veteran of World War I and served in the 542nd Engineers. This is where the process took its first turn. There are few records available in Ancestry or Fold3 connected to Okey Ogden’s military service. However, there was a digitized request form for his military headstone after his 1953 death (his grave and headstone are in East Oak Grove Cemetery in Morgantown, WV). The person who requested Ogden’s headstone was Mrs. Linnie M. Slaughter, the proprietor of the Green Book site at 3 Cayton Street. Somehow Slaughter and Odgen were connected. According to the scanned map cards digitized by the Monongalia County Assessor’s Office, Lizzie M. Slaughter acquired the plot for 1046 College Ave in 1953, the same year that Okey Ogden died. When I delved into the parcel maps and tax records for Cayton Street I discovered that Linnie M. Slaughter’s name was on all three plots of land, along with Jennette O. Parker. At this point I knew that all three structures were extant, expanding my project from one HPI form to three, and all three proprietors were connected in some way. The difficulty in connecting Ogden, Parker, and Slaughter together was the different last names. I knew that Slaughter and Ogden were directly connected because Slaughter had requested Ogden’s headstone. However, after about an hour of searching I could find no record of Slaughter’s marriage to Charles William Slaughter to determine her maiden name. The break-through came after switching to focus on Jennette O. Parker. In the tax map cards Parker was always listed together with Grace Edwards, who I determined was Parker’s daughter. By following Parker and Edwards backwards through the census records I determined that Linnie M. Slaughter’s maiden name was Edwards; Grace and Linnie Mae were sisters from Jennette Parker’s first marriage to Charles Edwards. Parker was her married name from her second marriage to Hartley Thomas Parker. I was able to trace Jennette Parker through her first marriage record to Edwards and discovered that her maiden name was Ogden. Jennette O. Parker was Okey Ogden’s sister. Considering how often Green Book sites are lost due to demolition, extensive changes, or poor documentation it was amazing to find this cluster of three extant sites all together and discover how they were all linked to members of the same family. Okey Ogden’s tourist home only operated between 1949 and 1952; these were the years between the death of his mother (who owned the home prior) and his own death in 1953. However, Jennette O. Parker and Linnie M. Slaughter continued to run their tourist homes into the 1960s when the final edition of the Green Book was published. As I continue to work on the HPIs I hope to dig further into local records to piece together more of the lives of this family that committed themselves to providing safe lodging for black travelers for more than a decade. Katie ThompsonDr. Katie Thompson is a Preserve WV AmeriCorps member serving with Clio during the 2020-2021 program year.

How do you do historical research for a site few people previously considered historical? This was the question I was faced with when my program director at Preserve WV AmeriCorps, PAWV's national service initiative, put out a call for volunteers for a new project. The project centered around The Negro Motorist Green Book, a series of African-American travel guides published by Victor Hugo Green. The Green Books, as they were colloquially known, were published from 1936 to 1966. They listed locations for black travelers to eat, stay, and socialize without fear of complications or danger. Early editions of the Green Book contained places Victor Green knew of or had heard about through his travels as a New York City mailman. As the popularity of the guides grew, readers began submitting their own information; by 1949 the Green Book contained hundreds of entries spread across every contiguous state.

One complication to consider was changing addresses. Hotel Capehart in Welch initially had the address 14 Virginia Avenue, but the name of Virginia Avenue has been changed to Riverside Drive. Other locations moved from one site to another. Moss’s Garage in Beckley was located at 501 South Fayette Street for many years before moving to 135 South Fayette Street. Finally, one of the most common types of entry in the Green Book was private residences willing to rent a room. The homes of normal regular people rarely command attention or recognition, making finding these homes a tall order.

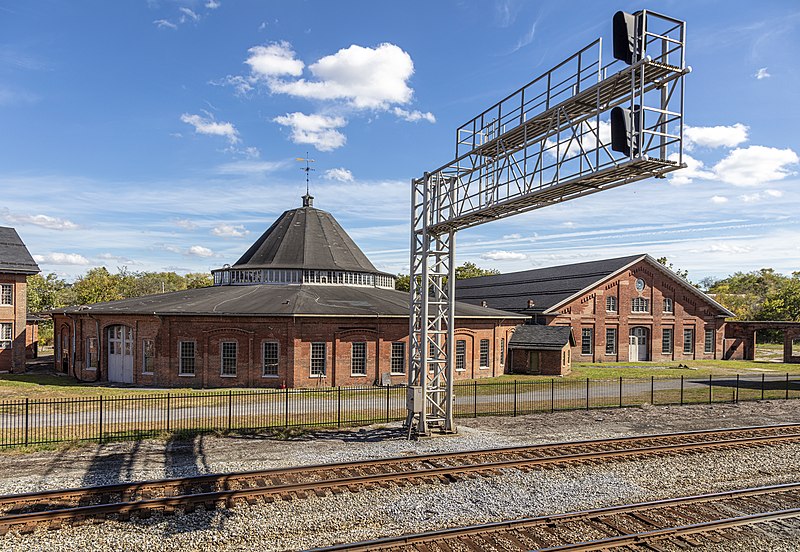

I employed several methods in my attempts to locate West Virginia’s Green Book sites. One helpful tool was comparing copies of the Green Book from different years to look for changes in address or operation. Historical city maps showing street names were similarly helpful when contrasted with modern ones. However, by far the most effective tool at my disposal was Google Maps. Beyond simply providing address information, the satellite imagery and street view technology were huge boons. Satellite imagery allowed me to check if a building was still standing, while street view let me see locations as if I were actually there. If the streetview of an address showed a modern office building, it was pretty safe to conclude that the Green Book site was demolished. Likewise, when the streetview showed a building that looked relatively older, it was often possible to use architectural clues to narrow down if the building was once a Green Book site. My work was primarily a broader overview that set the stage of other AmeriCorps members to dive deeper into the history of specific Green Book sites. Iain MackayIain MacKay is a West Virginia native and WVU graduate serving with Clio through Preserve WV AmeriCorps. In March of 2018, Bryson VanNostrand of VanNostrand Architects approached me at a conference with a very intense “suggestion”. He told me to make sure I let the City Manager know that Hinton HAS to do something with the Hardwoods Building. He then later spoke on a panel at the conference. Everything he talked about on the panel spoke to me. He was my type of community leader! Being very new to Hinton and to the Economic Development Scene, I really didn’t know which building he was talking about. I had recently submerged myself in the land of Volunteerism, and this was just another conference I was adding to the list in hopes of understanding what I need to do here. What was my calling? Shortly after, coincidentally, Hinton was offered some Technical Assistance Funds through the West Virginia Community Development program HUB CAP. Our team was huddled around a table coming up with ideas. I suggested getting the Hardwoods Building structurally analyzed. For some reason, this mission was burned in my brain. The team was supportive, the building was in need, and I knew just the person that had the heart in the project. I learned then, not everybody is into historic preservation. I didn’t even know it was important to me. I was just merely following through with a firm suggestion and happened to be in a position to get it done. I also knew if anybody was going to do it and do it right, it would be VanNostrand Architects. About a year later, through all of my volunteer work, an AmeriCorps opportunity with the Hinton Historic Landmarks Commission opened up. This was such an important move for me. I was now able to focus on all the work I had been doing, and in a capacity to see more projects get done! To get compensated for doing dream work, is an absolute dream! The Hardwoods Building never left my sight. I dug for hours to find any and all information on this structure. It was historically known as the New River Grocery and is located in Hinton’s heart of the Railway Development District. This structure has been identified as the 6th most important historic structure in the Hinton Historic District to be rehabilitated. It is a three-story brick and timber structure, and was originally built as a grocery House, hence the New River Grocery. What it’s most known as to the community, was a roller rink back in the 60’s, 70’s and 80’s. Lots of people remember going on their first dates here, birthday parties, and skating for hours and hours, Great memories were made on every inch of that property. Most recently it housed a woodworking shop, specializing in garden needs, called New River Wood. When this tenant vacated, they left all their woodworking equipment. Most of the equipment was not useful to hobbyists, seeing as they were machines built for high power. By now, the City of Hinton had acquired the property. The City also had no use for the equipment, and it was just sitting in the way of helping visualize what a great space this could be! Among the heavy duty machinery, there were what seemed like decades of saw dust, and just overall mess. I have come to the conclusion, I may be the only person interested in preserving this building. The City didn’t have capacity to seek funding, and this poor building sat vacant. Deteriorating more every single day. Every rain drop that fell, compromised the structure just a little bit more. The roof was failing quickly and something needed to be done fast. In efforts to make the building more appealing to anyone that was in the right position to listen, I happily offered up to clean the building up as my AmeriCorps Civic Service project. I figured it would be easier for people to understand the beauty of the building if it looked nicer. Plus, the effort was relatively free for the City. Win! Win!! After a successful clean up, I then took inventory of all the equipment. Being that it was City property, an auction would have to take place. I was crossing my fingers, hoping there would be enough money generated to help stabilize the building. I was sorely wrong. The money raised was just a drop in the bucket. However, there were lots of new owners of old equipment that got an extremely great deal on really expensive pieces. By this time, I am feeling defeated. I did not know what to do. Fortunately, I attended a Summit about a month after the Auction and ran into our old community Coach with the HUBCAP program, Kaycie Stuschek. She suggested applying for the Development Grant with the State Historic Preservation Office. It was due in about a month, which wasn’t much time, but I knew I could get this done. Up to this point, I had loads of information, pictures, stabilization quotes, everything I could possibly need! Now it was time to write my first big girl grant! The grant application was accepted. Covid happened. It took almost a year to receive the Bid package and get things moving in the direction we have been shooting for. During that year, the building crumbled more. I had thought the previous condition was bad until I walked in recently. It became worse, in the matter of a few months. Thankfully, I had my trusty ol' architect, Bryson, lend me an hour of his time to see what damage had been done. It wasn’t good. However, there is light at the end of the tunnel. I am currently writing another grant application to hopefully secure 100 % of the funds to get the deterioration to come to a complete stop. Meanwhile, we will soon be accepting bids to fulfill the first round of grant money. This has been a long process. Lots of faith, patience, and work has taken place. Maybe this is why historic preservation isn’t for everyone? I am bound and determined though to save this structure! The Hardwoods Building is extremely important to how Hinton became the booming town it once was. In my mind, this building could do it again for another century, but probably more like two. If you are interested in donating to this project, you can send a check to City Hall c/o Hardwoods Stabilization 322 Summers St. Hinton, WV 25951 CANDICE HELMSCandice Helms is a Preserve WV AmeriCorps member serving with the Hinton Historic Landmarks Commission. My name is Candice Helms. I am currently serving my 3rd term as an AmeriCorps Member with Preserve WV. AmeriCorps has been an instrumental part of me establishing this new community as my own. It has helped me be part of the "greater good" in efforts to help provide my son with a bright future within the community. Of all my Civic Service Projects I have done, cleaning up the Esquire Cemetery has been the most fulfilling project to date. Esquire Cemetery was deeded to the trustees of the town of Hinton in 1892. It was established that this would be a "colored" cemetery. On December 12, 2020, the day I conducted this project, about 25 people came out and really uncovered a great deal of History. There were Veterans' graves that haven't seen the light of day. Veterans as early as the Spanish American War. There were also prominent doctors, pastors, and relatives of community members that live here today. This project has organically spun into other projects. For instance, I highlighted a handful of some of the people buried in the Cemetery on the FB page I created. The posts generated lots of memories from around the community and also had an overall positive vibe. From these posts, I keep learning the History and have made relationships that have invested time to helping the Black Community preserve their, OUR, History as it happened. Candice HelmsCandice has served as a Preserve WV AmeriCorps member with the City of Hinton's Historic Landmarks Commission between the years of 2019 and 2021. When I first started my service term at the Martinsburg Roundhouse, I was familiar with historic tourism but I didn’t know anything about the roundhouse. Though I grew up in Martinsburg I had only visited the building once for a local festival. I didn’t really learn any of the roundhouse’s history until I started my service. Prior to meeting the site supervisors at the interview, I didn’t know anyone who volunteered or knew a lot about it. The first project assigned to me at the Martinsburg Roundhouse was to create an inventory of the numerous artifacts housed at the site. It is also the project I have worked on the longest and there are a few remaining artifacts that need to be tagged. When I started this process I felt overwhelmed. There are hundreds of items and documents stored at the Martinsburg Roundhouse. And new artifacts come into the site a couple of times a month, typically donations made by family members whose fathers and grandfathers worked at the roundhouse. Creating an inventory and tagging artifacts at the roundhouse has involved looking at lots of railroad spikes and railroading tools. I occasionally have been completely stumped about what an object is. Part of the process of researching and identifying the unknown objects at the roundhouse has been the extensive use of Google Lens and online railroad tool catalogs. During this project, one of my favorite ways to identify artifacts has been by collaborating with past and current railroad employees. One of the people I have talked to about the variety of tools and objects at the roundhouse is Jim. Jim worked at the Martinsburg Roundhouse from about 1949 until 1985 when jobs were moved from Martinsburg to Barboursville. During his visits to the roundhouse, Jim has identified several objects. Some of the more peculiar pieces, the ones that he struggled to or wasn’t able to identify, he told me were specialty made at the Martinsburg shops to address a specific need at the time. Another person who has been helpful as I attempt to name these objects is Mark. Mark works for CSX and is supervising an ongoing project in Martinsburg, and is frequently on the roundhouse property. Yet Mark’s connections to the roundhouse are deeper than working for CSX, Mark’s great-grandfather worked at the Martinsburg Roundhouse shops. Throughout the late summer and early autumn, he has made several visits to the roundhouse, including coming on a tour of the site with his mother and daughter. During his visits to the roundhouse, Mark has been incredibly helpful in identifying the artifacts housed in the roundhouse. One day I was losing my mind trying to figure out what an object was. My running theory was that it was a bucket from a digging tool. I was exhausting my enthusiasm for research by scrolling through website after website. Then Mark walked into the office, picked up the object, and casually told me that what I was looking at was a rail brace, which sits against the rail supporting it. Mark has been helpful in other ways. He also brought in a retired railroad worker, Stevie. Stevie helped me identify some of the more challenging artifacts at the Martinsburg Roundhouse. The volunteers and board members care immensely about the artifacts at the roundhouse. Volunteer and tour guide, Mike Giovannelli, brims with excitement every time he leads a group into the site’s artifact room. Yet I have found that some of the people who care the most about the artifacts are those who have worked on the railroad.

Claire TryonClaire served as a Preserve WV AmeriCorps member with the Berkeley County Roundhouse Authority during the 2019-2020 program year. There’s no Place like Thurmond: Historic Preservation in West Virginia’s Smallest Incorporated Town10/19/2020

At about 5:30 on the second Wednesday of every month this year, I walked across the New River from my house in Dun Glen to attend a town meeting in Thurmond. Once there, I joined with the town’s five permanent residents to discuss town business over dinner in Thurmond’s one-room town hall. We approved the minutes from our last meeting, went over the town’s budget, and discussed plans for upcoming town projects and events. Sometimes our meetings were interrupted by a train passing by on the tracks just a stone’s throw from our meeting place. In that event we all filed outside to wave at it as it made its way through town. Once the train passed by and the noise subsided, town meeting would resume in West Virginia’s smallest incorporated town. Though Thurmond is an incredibly small town, it cannot be described as sleepy. The people of Thurmond take great pride in their community. This year alone, they repaired their Main Street, installed new town banners, and started making plans to build a municipal sewer system. On top of that, they do light maintenance and mowing in the town’s public spaces and host an annual litter pick-up event called Thurmond Clean-up Day. In years not affected by a global pandemic, they host a triathlon and a family festival called Train Days. The people of Thurmond are not alone in their efforts to care for their town. The National Park Service owns most of the property in Thurmond, including about 20 historic buildings. As an AmeriCorps member serving at the New River Gorge National River, I was involved in a project to develop a historic preservation field school using Thurmond as the “classroom” where participants will learn how to care for historic buildings. Over the course of the year, we developed a plan for our project, presented our ideas to the park’s leadership team for their approval, and contacted colleges to gauge their interest and ask them to participate. Between December and October, PAWV's executive director, Danielle Parker, alongside myself and Park Staff made great strides toward getting the project off of the ground; the project was approved at the park level, and we have six colleges interested in partnering with us in this project. The next steps will involve more in depth and specific planning and coordination to determine how we will work with colleges, and what work we will accomplish together. Working on this field school project was an incredibly gratifying part of my term here at the New River Gorge. Not only because of how the project is coming together and how promising it is, but also because it has been a way for me to play a role in caring for the town of Thurmond, just as its residents do. Will WheartyWill Whearty was the Preserve WV AmeriCorps member at the New River Gorge National River during the 2019-2020 program year. |

Preserve WV StoriesCategories

All

Archives

August 2023

|

Get Involved |

Programs |

Contact UsPreservation Alliance of West Virginia

421 Davis Avenue, #4 | Elkins, WV 26241 Email: [email protected] Phone: 304-345-6005 |

Organizational Partners:

© COPYRIGHT 2022 - PRESERVATION ALLIANCE OF WEST VIRGINIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed